Ballistic vs. Plyometric: Understanding Dynamic Movements

Have you heard the Russian proverb, “once you stop jumping, you start dying”? A little dramatic and fatalistic maybe, but the basic idea centers around maintaining your body’s capacity to perform explosive plyometrics. As we age, we become more risk-averse — injuries take longer to heal. Keeping up your ability to jump and land can stave off decrepitude.

Fred Ormerod is a freelance coach, army reserve medic, nurse, master’s student, and massage therapist. He’s spent a decade working in healthcare and five years coaching in one of Edinburgh’s leading training facilities.

What Are Plyometrics?

Plyometrics are exercises that stimulate the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC).

There are two elements to this:

- Elastic elements (fascia and tendons)

- Contractile (muscle) element

Imagine the human body is a mattress spring (or Hookian spring if you’re into physics) — if you compress it or stretch it, the spring will recoil back, just like when we perform a jump. During this jump we have three phases which you might have heard of:

- The eccentric phase – where the spring stretches (think EE-longate), this is the downward motion of a jump as we load or ‘pre-stretch’ the muscles

- The amortization phase – the brief period between phases, don’t worry about this one, I never do.

- The concentric phase – where the spring CON-tracts, or we jump.

The two elements combine in these three phases to produce a force at a certain speed. The harder the muscles pull on the elastic elements the greater the force, they can also contract faster or slower, and this is influenced by how elastic or stiff the other elements are.

Why Should You Jump?

As athletes it is important to improve upon this elastic recoil in our training. Running faster, jumping further and hitting harder are all good enough reasons for this.

As you’d expect, improvements can be found by increasing the size of muscles (contractile), tendons (elastic) and absolute contractile force through simple strength training. However, we want to get really explosive and fast in our training/sport and doing so can help reduce the risk of many common injuries as well.

The Strength-Speed Curve

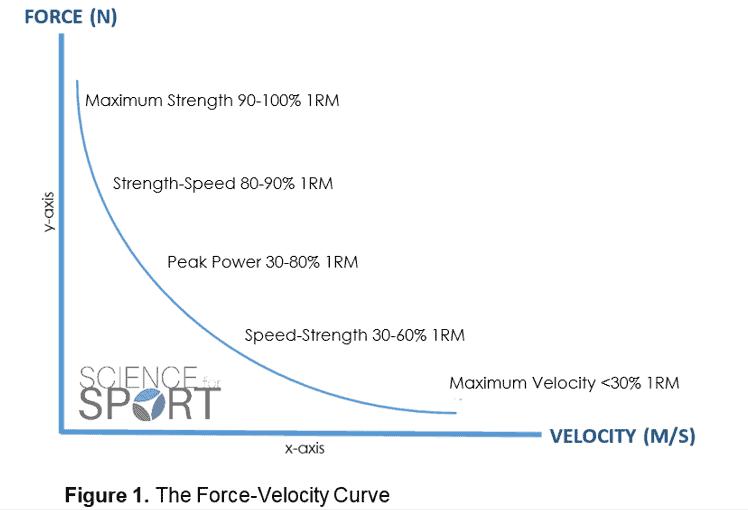

There is a spectrum of stimuli you can glean from training movements under different loads and at different speeds. Depending on your needs as an athlete, it’s wise to train specifically for that need. For instance, if you’re a powerlifter, you might want to focus primarily on the strength, maybe strength-speed portion of the curve. If you’re a ballet dancer or a fancy, flying, foot-working footballer, the speed-strength end of the curve might be more prominent in your training.

The strength-speed curve above details what zones you might want to train in for your specific purposes, once you’re sure you need to. A lot of athletes should aim to live in the middle unless you are sport-specified.

It is worth bearing in mind that your power output will always be limited by your maximum strength output. As such, you might be better spending your time simply getting stronger. As a rough guide, if you’re unable to squat or deadlift your body weight and bench press at least 75% of your bodyweight, then it’s a good idea to improve upon that before you spend too many hours of your training week on any of the ballistic/plyometric movements detailed here.

In fact, if you don’t see improvements in your ballistic outputs after training with these movements for an extended period (i.e. you can’t throw or jump further or faster than before) it’s likely because you’re limited by strength rather than the ability to perform movements quickly.

Assuming you’re strong enough to warrant including ballistic or plyometric training (and it’s worth getting help in continually assessing this) let’s have a look at what this training can do for you.

What is Ballistic Training?

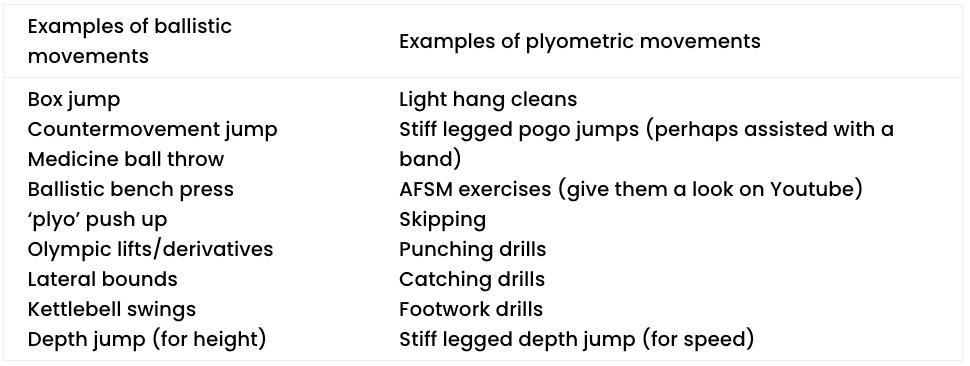

Dynamic jumping movements are divided into two categories to avoid confusion and put each to their proper use. These are long (ballistic) and short (plyometric) response exercises.

Ballistic training is high velocity (fast moving) often with maximum (or close to) intent. The purpose of which is to build strength-speed in athletes.

There are multiple benefits in sports for training ballistic movements:

- Muscle hypertrophy (mostly in people new to training)

- Increased muscle fiber contraction force

- Improved muscle contraction speed

All of which tend to lead to improved performance in training tests, strength tests and competition performance.

Injury prevention

Up to 50% of runners experience knee pain. Up to 32% of runners experience lower leg pain and 38% deal with upper leg pain. Common injuries include runner’s knee (patella femoral syndrome), shin splints, hamstring pulls, and Achilles tendonitis.

Where the stress level applied to tendons exceeds the tensile strength of the tendon is a risk for injury. Strength training helps mitigate this issue and allows you to gradually increase the intensity of your runs.

It’s now widely accepted that working on your overall physical strength helps prevent these kinds of injuries. Athletes who can back squat 1.5x bodyweight radically reduce their risks of running-related injuries. It’s worth noting that runners who land on their forefoot and focus on the eccentric loading of the calf muscles (going slow as calf muscles stretch) are also less prone to injuries.

Suggested exercises

Not sure where to start? Here’s a list of exercises that running athletes should consider incorporating into their program if they want more running power and bulletproof knees and hips:

SQUATS

The ultimate lower body builder, weighted squats can reduce your risk of injury and boost your sprinting power by strengthening your glutes, quads, and hamstrings. They also help develop upper trunk and core strength with efficient bracing and shoulder tension.

LUNGES

These are a MUST to include in any running program— high volume lunges build muscular endurance, while heavy loads build unilateral strength. Work on those imbalances and get your glutes strong with weighted lunges.

CALF RAISES

Again useful to help build muscular endurance and avoid injuries. Strong calves are an important muscle group in controlling what is known as the Windlass mechanism as the foot contracts to propel athletes forward fast.

LOAD-BEARING ROTATION

Exercises that include rotation are important since every step whilst running uses minor rotations in the body that might lead to injury without proper training. Key areas to consider here are torque at the knees, hips and in the lower trunk. Exercises to target these areas might include: leg extensions, hip adduction/abduction and pallof press/cable chops to strengthen the core through rotation movements. Back extensions or deadlifts can also be incorporated to help support the lower back.

NORDIC CURLS

These might seem scary at first, but they’re a great exercise to eccentrically load the hamstrings at both ends (knee and hip). The science available suggests incorporating as few as 8 effective reps per week might help in supporting healthy hamstrings.

HIP THRUSTS

Developing strong glutes helps athletes apply the most force to the floor while propelling themselves forward. That’s exactly what you’re doing when loading your hips during hip thrusts. The fastest Olympic sprinters have well-developed glute muscles. (A bigger booty never hurt anyone.)

OLYMPIC WEIGHTLIFTING

Olympic lifts are an awesome way to increase your strength and power. For those starting out in strength training, they may seem a little advanced. But breaking them down into smaller components can be just as effective at increasing your power. These simpler movements avoid the catching phase, which improves performance and speed for any non-Olympic lifting athlete. Examples include: mid-thigh pulls, clean high pulls, and jump shrugs.

PLYOMETRICS

Going along with the theme of producing force off the ground, plyometrics (not to be confused with ballistic training, like box jumps or Olympic lifts) incorporate training where contact time (or intended contact time) doesn’t exceed 250 milliseconds. This helps to condition a runner’s tendons for multiple impacts. Be careful with this one, and be sure you’ve got a reasonable level of strength already to avoid training injuries.

A strength training plan for runners

If you’re ready to start using strength training work to bolster your abilities as a runner, here is a suggested week you can work in with 2-4 runs:

Session 1:

Squat – 5×5 @RPE 8

Lunges – 4×6 each side @RPE8

GHD Back Extensions – 3×10 @RPE8, 2-0-0-0 Tempo

Pallof Press – 3×10 @RPE 8, 2-0-2-0 Tempo

Calf Raises – 3×15 @RPE 8, 3-0-0-0 Tempo

Session 2:

Trap Bar Deadlift – 5×5 @RPE 8

Goblet Side Lunges – 4×6 each side @RPE8, 3-0-0-0 Tempo

Nordic Curls – 4×3 @RPE8, Max-0-0-0 (concentric phase not required, wriggle up as needed)

Pogo Jumps – 15 reps EMOM 10 minutes @RPE 8, These can be band assisted to reduce impact if just starting/worried about achilles

The best way to progress this simple program is to increase the weight you use over time. This might look like linear progression at first (adding 5-10lbs each week), but should also include some de-load weeks (with lower weights) around weekly runs. Since the intended stimulus for these sessions is strength, you could do fewer reps at higher weights.

Varying the exercise tempo (speed) is a useful and underutilised tool for many athletes in this scenario, too. Increasing the time under tension helps boost muscle stimulation when you’re still too green to go heavy. Eccentric and isometric training has been shown to improve outcomes for those suffering from and trying to prevent injuries as well.

As always, be mindful of your form and the complexities with these exercises. If you’re looking to improve your running with some strength work, it’s well worth building gradually. It defeats the purpose of preventing injuries if you end up pulling a hamstring.

Something to keep in mind: the chances of injuring yourself through proper strength training are slimmer than you might think. It’s also worth seeking some 1:1 assistance (via a personal trainer) to look out for any specific imbalances in your strength or gait. A good coach should be able to keep your goals in mind and get you moving in the right direction.

About the author

Fred Ormerod is a freelance coach, army reserve medic, nurse, masters student, and masseuse. He’s spent a decade working in healthcare and five years coaching in one of Edinburgh’s leading training facilities. Fred has helped clients trying to walk again, serving in the military, competing on the world’s strongest stage, and in other Olympic-style events. With a holistic training philosophy at his core, he feels any and all training goals are accomplishable with consistency.

Have you heard the Russian proverb, “once you stop jumping, you start dying”? A little dramatic and fatalistic maybe, but the basic idea centers around maintaining your body’s capacity to perform explosive plyometrics. As we age, we become more risk-averse — injuries take longer to heal. Keeping up your ability to jump and land can stave off decrepitude.

Fred Ormerod is a freelance coach, army reserve medic, nurse, master’s student, and massage therapist. He’s spent a decade working in healthcare and five years coaching in one of Edinburgh’s leading training facilities.

What Are Plyometrics?

Plyometrics are exercises that stimulate the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC).

There are two elements to this:

- Elastic elements (fascia and tendons)

- Contractile (muscle) element

Imagine the human body is a mattress spring (or Hookian spring if you’re into physics) — if you compress it or stretch it, the spring will recoil back, just like when we perform a jump. During this jump we have three phases which you might have heard of:

- The eccentric phase – where the spring stretches (think EE-longate), this is the downward motion of a jump as we load or ‘pre-stretch’ the muscles

- The amortization phase – the brief period between phases, don’t worry about this one, I never do.

- The concentric phase – where the spring CON-tracts, or we jump.

The two elements combine in these three phases to produce a force at a certain speed. The harder the muscles pull on the elastic elements the greater the force, they can also contract faster or slower, and this is influenced by how elastic or stiff the other elements are.

Why Should You Jump?

As athletes it is important to improve upon this elastic recoil in our training. Running faster, jumping further and hitting harder are all good enough reasons for this.

As you’d expect, improvements can be found by increasing the size of muscles (contractile), tendons (elastic) and absolute contractile force through simple strength training. However, we want to get really explosive and fast in our training/sport and doing so can help reduce the risk of many common injuries as well.

The Strength-Speed Curve

There is a spectrum of stimuli you can glean from training movements under different loads and at different speeds. Depending on your needs as an athlete, it’s wise to train specifically for that need. For instance, if you’re a powerlifter, you might want to focus primarily on the strength, maybe strength-speed portion of the curve. If you’re a ballet dancer or a fancy, flying, foot-working footballer, the speed-strength end of the curve might be more prominent in your training.

The strength-speed curve above details what zones you might want to train in for your specific purposes, once you’re sure you need to. A lot of athletes should aim to live in the middle unless you are sport-specified.

It is worth bearing in mind that your power output will always be limited by your maximum strength output. As such, you might be better spending your time simply getting stronger. As a rough guide, if you’re unable to squat or deadlift your body weight and bench press at least 75% of your bodyweight, then it’s a good idea to improve upon that before you spend too many hours of your training week on any of the ballistic/plyometric movements detailed here.

In fact, if you don’t see improvements in your ballistic outputs after training with these movements for an extended period (i.e. you can’t throw or jump further or faster than before) it’s likely because you’re limited by strength rather than the ability to perform movements quickly.

Assuming you’re strong enough to warrant including ballistic or plyometric training (and it’s worth getting help in continually assessing this) let’s have a look at what this training can do for you.

What is Ballistic Training?

Dynamic jumping movements are divided into two categories to avoid confusion and put each to their proper use. These are long (ballistic) and short (plyometric) response exercises.

Ballistic training is high velocity (fast moving) often with maximum (or close to) intent. The purpose of which is to build strength-speed in athletes.

There are multiple benefits in sports for training ballistic movements:

- Muscle hypertrophy (mostly in people new to training)

- Increased muscle fiber contraction force

- Improved muscle contraction speed

All of which tend to lead to improved performance in training tests, strength tests and competition performance.

What is Ballistic Training?

Plyo work involves high velocity training with typically lower loads. They’re usually programmed to help improve speed-strength and reactive strength in athletes. The key element is fast contraction speed. What you’re looking for is a fast change from eccentric to concentric movements. Some scientists go so far as to classify plyometric contraction as anything below 0.25 seconds and the stimuli you gain from performing them regularly differ slightly to ballistic movements:

- Increased tendon elasticity

- Increased tendon stiffness

- Reduced time for eccentric loading in jumping movements and in change of direction (you can jump and change direction faster without having to ‘pre-stretch’ muscles as much)

- Reduced risk of injury due to increased tendon strength and stiffness

You might find that some jumps you do are ballistic in nature; you dip into them slower and jump further. Others are plyometric; you dip down as fast as possible so the muscles and tendons don’t have the same elastic recoil and you don’t jump as far (but you might change direction quicker).

What is Plyometric Training?

Plyo work involves high velocity training with typically lower loads. They’re usually programmed to help improve speed-strength and reactive strength in athletes. The key element is fast contraction speed. What you’re looking for is a fast change from eccentric to concentric movements. Some scientists go so far as to classify plyometric contraction as anything below 0.25 seconds and the stimuli you gain from performing them regularly differ slightly to ballistic movements:

- Increased tendon elasticity

- Increased tendon stiffness

- Reduced time for eccentric loading in jumping movements and in change of direction (you can jump and change direction faster without having to ‘pre-stretch’ muscles as much)

- Reduced risk of injury due to increased tendon strength and stiffness

You might find that some jumps you do are ballistic in nature; you dip into them slower and jump further. Others are plyometric; you dip down as fast as possible so the muscles and tendons don’t have the same elastic recoil and you don’t jump as far (but you might change direction quicker).

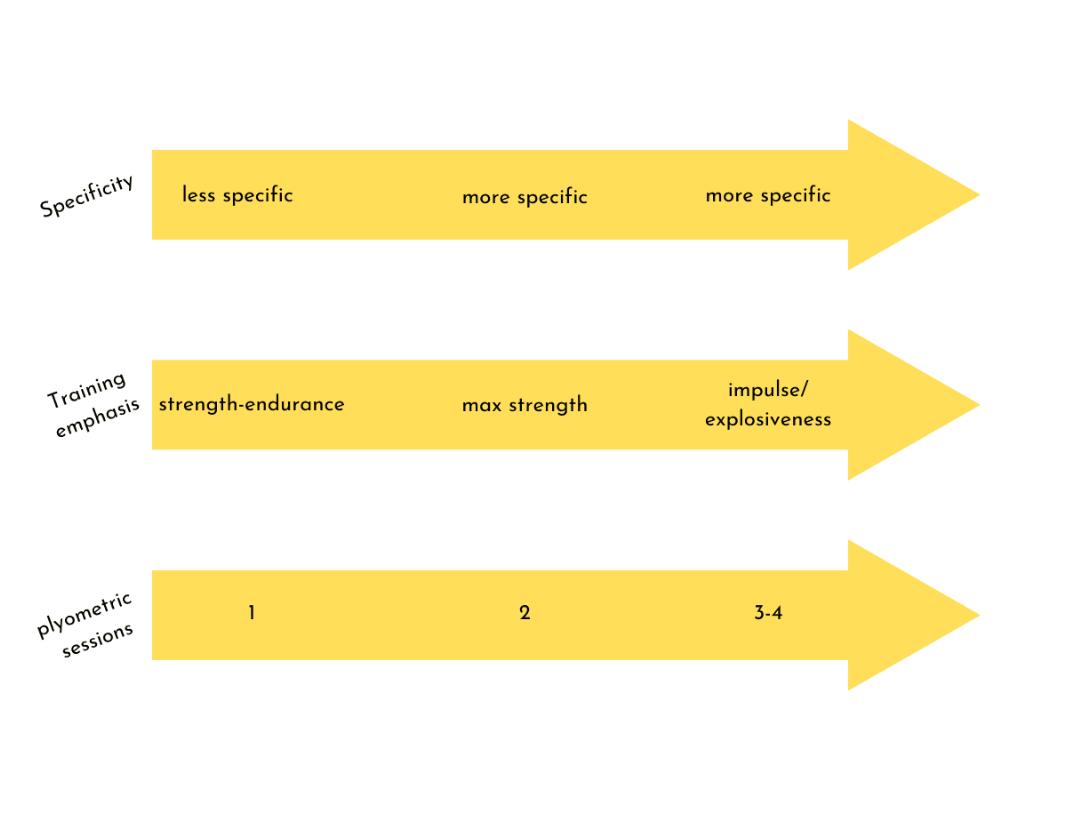

How Do I Program Plyometrics & Ballistics?

Proper periodization is very important. Below you’ll find a table highlighting how much plyometric work to include in your training at different stages of a training plan:

It’s generally suggested that you should have 48-72 hours between intense plyometric training sessions, meaning about 2-3 times per week depending on your schedule.

It’s worth considering how many contacts you absorb per training week since introducing high volume can lead to severe delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) and even tendonitis. Starting out at 80-100 contacts per week and building to 120-140 as you progress is advised. You’d do well to include any sport specific training into this count as well. I’ve learned this from experience in coaching elite fencers who absorb hundreds of contacts through their lead leg and do not need extra intense training sessions during which they absorb more force.